On the Pursuit of Happiness

There's a photograph from 1945, depicting a sailor kissing a nurse in Times Square, Victory over Japan Day. The streets are flooded with confetti and people, strangers embracing one another, champagne flowing from windows, four years of apocalyptic war finally over. If you've seen the image, you know what it captures: pure, unrestrained happiness. The kind that bursts from your chest. The kind that makes you want to burst into dance. The kind that makes you kiss strangers in the street.

That sailor, George Mendonsa, lived another 69 years. He married. Raised children. Worked. Retired. By all accounts, he lived a good life.

But was he ever that happy again?

None of them were. How could they be? That moment was spontaneous, unrepeatable, electric. It was filled with relief and victory and youth... And it was gone the not very long after it arrived. The next day, there were bills to pay. Jobs to find. Marriages to navigate. The ordinary weight of living, pressing back down like gravity after a long, difficult campaign ending on a spectacular moment of flight.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness...

Among all the feelings a person can have, we have come to hold one specific feeling higher in regard than others: Happiness. It is the only emotion that is written into the very architecture of nations. It is the ultimate justification, if you're doing something, let's say, suboptimal, "as long as you're happy" applies. It excuses the irrational, redeems the impractical, and sanctifies the selfish. We treat happiness as a moral compass the measure by which all choices are appraised.

We've constructed an entire industry around it: self-help gurus are out there promising their new five step formula to lasting happiness, pharmaceutical companies are medicating its absence, advertisers will sell it to you in different forms: pills, gym memberships, luxury cars, social media likes... Heck, we measure national wellbeing by it. We judge our own lives by it. We wake up each morning and ask ourselves: Am I happy? And when the answer is no - and it so often is - we assume we've failed.

I. THE FLEETING NATURE OF HAPPINESS: CIRCUMSTANTIAL, CONDITIONAL, FRAGILE

Happiness requires the right conditions. The right circumstances. The right alignment of external factors. You get the job and you're happy. Then, slowly but surely, you start to resent the job. You may then lose the job or not, but happiness surrounding it has been long gone. You fall in love - you're happy. After some months, or perhaps years however, when you're no longer excited about picking up your partner's dirty socks off the floor, you realize that happiness hasn't knocked on your door for a while now. You buy the house, and for a few weeks, maybe months, you feel it. Then the feeling fades. The house is just four walls. The promotion is just your old job with extra steps. The achievement you spent years working toward gives you a weekend of satisfaction, and then it's Monday again. Bzzt bzzt. It's 6 am. Time to wake up.

This is the nature of happiness itself.

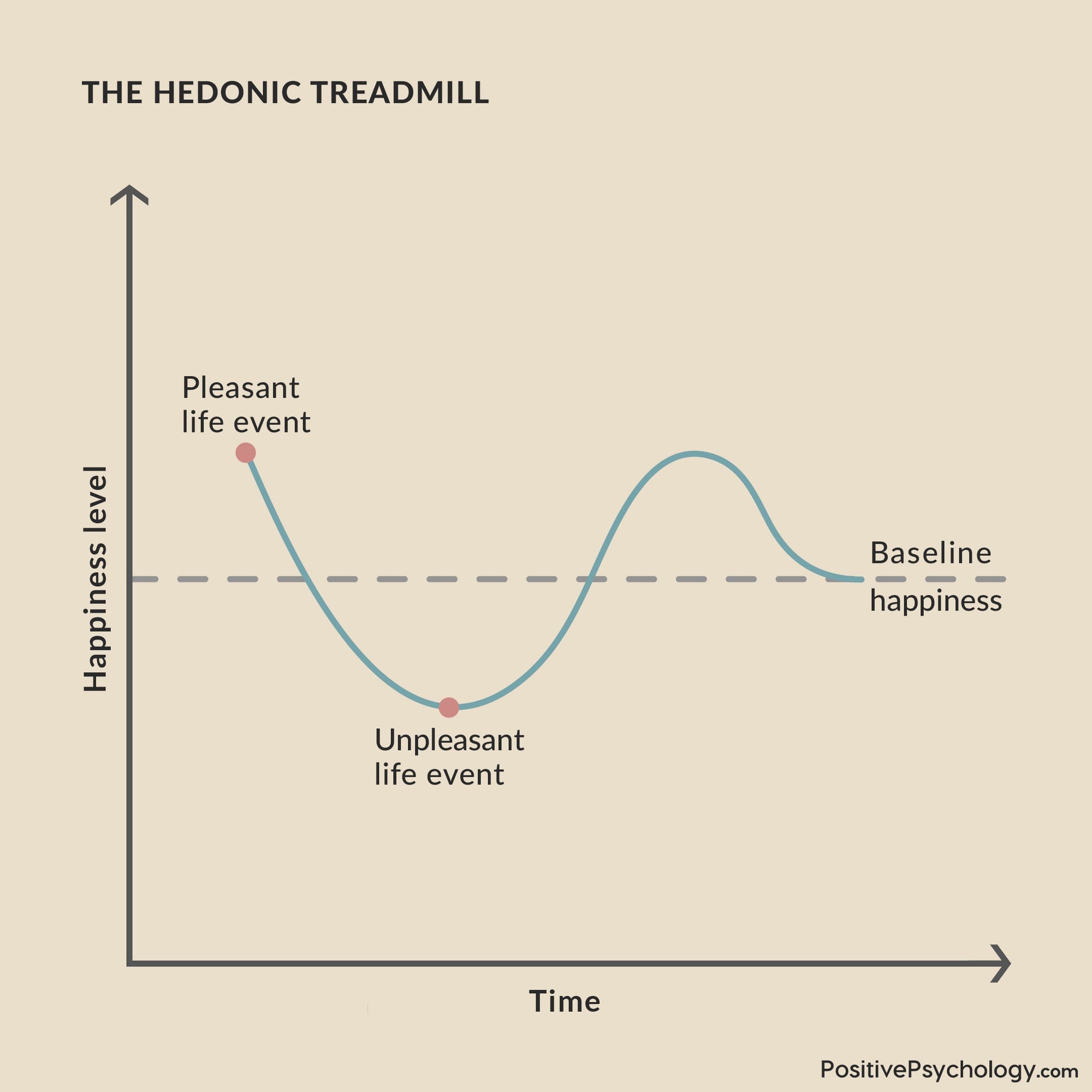

There's a term for it: the hedonic treadmill. It's the phenomenon where humans return to a baseline level of happiness regardless of what happens to them. Lottery winners and newly paralyzed accident victims end up at roughly the same happiness level within a year. Both of them. The person who won millions and the person who lost the use of their legs settle back to almost the same emotional baseline after a while.

Because the mind adapts, even to extremes. We normalize. We habituate. It's automatic, unconscious, relentless.

The thing that made you happy yesterday is mundane today. The raise that felt like freedom in month one is just your salary by month six —and somehow you're still living paycheck to paycheck, still stressed about money, still wanting more. The relationship that gave you butterflies becomes routine. The promotion you'd have killed for two years ago is now just your job, complete with all the same frustrations and politics you had before, just with a different title on your email signature. Tous les mêmes. All the same.

And this is not cynicism. This is neurobiology. This is your brain doing exactly what it evolved to do.

Your brain doesn't care if you're happy. It cares if you're surviving and reproducing. Happiness is a tool —a neurochemical cattle prod that says "this is good, do more of this. This might lead to more survival and reproduction" But if that feeling stuck around, if you stayed satisfied after getting the thing you wanted, you'd stop. You'd settle. You'd become complacent. And way back in the environment we evolved in, complacent meant dead.

So your brain gives you a hit of dopamine, serotonin, whatever cocktail makes you feel good —and then it yanks it away. On purpose. The hedonic treadmill is a feature. It keeps you hungry. Keeps you moving. Keeps you chasing the next thing, and the next thing, and the next thing.

Which would be fine - adaptive, even - if we still lived in that environment. But we no longer do.

We live in a world that's figured out how to weaponize this mechanism. It's humans rising above biology again. The entire economy today runs on manufacturing dissatisfaction and selling you the solution. Get the car, get the house, get the body, get the life —and you'll finally feel the way you're supposed to feel.

Except you won't. Because your brain will adapt to that too. The new car becomes your car. The dream house becomes your house. The goal body becomes your body —and you'll find new flaws to fixate on, new goals to chase, because your brain literally cannot let you rest.

And here's the truly fucked up part: we know this. We're aware of this. The research is clear. The studies are conclusive. The hedonic treadmill is not a secret. And yet we keep running on it anyway. We keep believing this time will be different. This achievement, this purchase, this relationship —this will be the one that finally makes us happy.

It won't.

Not because you're doing it wrong. I want you to know this, it's not because you're ungrateful or not trying hard enough. But because the system - both the biological one and the economic one - is designed to ensure you never arrive. The treadmill doesn't have an off switch. The finish line doesn't exist.

So what do you do with that? Do you just... give up? Stop wanting things? Embrace some kind of ascetic monk lifestyle where you pretend not to care about anything? That's what some "gurus" might advise you to do. But I won't.

I won't. Because that's just another way of lying to yourself.

The point isn't to stop wanting. The point is to stop expecting wanting to end. Stop building your entire sense of self-worth and life satisfaction around achieving a state of permanent happiness that your brain is neurologically incapable of maintaining. Stop interpreting the inevitable fade of excitement as personal failure.

You're not failing. You're adapting like you're supposed to. Like every human who's ever lived has done.

The question isn't how to get off the treadmill because you can't.

Building your life around the pursuit of happiness is building your life around something that's designed to disappear.

The question is: knowing that you're on it, knowing that the feeling you're chasing will fade, knowing that you'll return to baseline no matter what you achieve... what do you actually want to do with your time? What's worth pursuing even if it won't make you permanently happy? What matters when happiness is off the table as the ultimate goal?

Because once you stop chasing happiness as the endpoint, you might actually figure out what you're actually after. And it probably isn't another hit of dopamine that'll be gone by next Tuesday.

II. THE WORD "HAPPINESS" IS LYING TO YOU AND YOU'RE LETTING IT

Let's talk about what "happiness" actually means. Because I don't think most people know. I don't think they've ever thought about it. And that ignorance is costing them. Ignorance always does.

The word "happiness" comes from "hap", Middle English for luck, chance, fortune. To be happy, etymologically, is to be fortunate. To have good hap. It's not a state you create or cultivate. It's a condition of external circumstance. You are happy because something happened to you. The universe rolled the dice in your favor. Sure, you might've increased your chances with the actions you took, but at the end of the day, you got lucky.

While this is fun trivia, this is also the word telling you exactly what it is: happiness is external. It depends on what happens to you. It is, by definition, out of your control.

Now to introduce another term which I will touch upon later: Contrast that with "joy." Joy comes from the Latin gaudium —a word tied not to circumstance but to exultation, to a kind of gladness that exists independent of what's happening around you. The Old French joie carried the same weight: a delight that wasn't contingent on your bank account or your relationship status or whether you got the promotion. A state of being, not a reaction to fortune.

These aren't the same thing. They were never supposed to be the same thing.

The Greeks had eudaimonia –constantly mistranslated as "happiness" when it actually means flourishing, living well, fulfilling your potential as a human being. And the critical part is: eudaimonia wasn't a feeling. It was a state of being that could include struggle, pain, loss, hardship. You could be suffering and still have eudaimonia if you were living according to your values and pursuing something meaningful. The Buddhists had mudita —sympathetic joy, the kind that arises from others' happiness and exists independent of your own circumstances. The Stoics spoke of apatheia —looks like apathy, but is a tranquility that endures regardless of whether fortune smiles on you or spits in your face.

Ancient cultures understood something we've forgotten amongst all the streamlining: there are different kinds of positive states, and they require different things, and confusing them is catastrophic. We cannot streamline emotions to get them ready for mass production, like we have done with countless other things.

Modern English flattened all of this. We took happiness, joy, contentment, fulfillment, flourishing, meaning, satisfaction – every distinct positive state humans can experience – and crushed them into a single, undifferentiated lump called "happiness." We lost the distinctions. We lost the nuance. We lost the ability to even name what we're actually after.

And in losing the language, we lost the ability to pursue what we actually need.

When someone says "I just want to be happy," what the hell do they mean? I'm sorry, but do you trust that you understand that want as they mean it? Do they mean they want good fortune? Better circumstances? Do they want a dopamine spike when they check their phone? A fleeting burst of pleasure? Or do they mean a sense of rightness, of purpose, of being aligned with something larger than their own hedonic treadmill?

They don't know. Because the language doesn't let them know. The word "happiness" has become so bloated, so vague, so all-encompassing that it's functionally meaningless. It's a target so broad you can't miss it and so empty that hitting it means nothing.

This isn't just confusion of semantics. It's existential confusion. People are building their entire lives around pursuing "happiness" without ever defining what that word means to them. Without distinguishing between pleasure and contentment, between excitement and peace, between having good fortune and living well.

And then they wonder why, after getting everything they thought would make them "happy," they still feel empty.

Because they were chasing a word. Not a thing they know. A linguistic ghost. A concept so diluted it lost all meaning.

You can't pursue happiness. At least not effectively. Not until you figure out what you actually mean when you say that word. Are you chasing pleasure? Contentment? Meaning? Purpose? Flourishing? Because those are different things. They require different strategies. Different sacrifices. Different ways of living.

The Greeks knew this. The Buddhists knew this. The Stoics knew this. We forgot it. Or more accurately, we let capitalism and advertising flatten our language until all positive states became "happiness," and happiness became something you could buy, something you could achieve, something that would finally arrive if you just worked hard enough and wanted it badly enough.

But etymology doesn't lie. Happiness is hap. It's luck. It's circumstance. It's external. And no amount of self-optimization, no amount of positive thinking, no amount of grinding is going to give you control over luck.

So stop chasing happiness. Start asking yourself what you're actually after. Give it a real name. A specific name. Because once you know what you're actually pursuing, you might have a chance of finding it.

III. EXPECTATION KILLS HAPPINESS—AND WE KEEP FEEDING IT ANYWAY

Here's what kills me about happiness: the idea of it is almost always better than the thing itself.

You know this already. You've lived it. That vacation you planned for six months —scrolling through photos, imagining yourself on the beach with a drink in your hand, finally relaxed, finally free. The anticipation was intoxicating. You could taste it. You could smell it. You were revelling in it. And then you actually went, and it was... fine, you guess. The hotel room was smaller than it looked online. You got sunburned. You spent half the time wondering if you should be enjoying it more. It was nice. But it was it the transcendent escape you'd built up in your head?

Or the wedding day. Years of planning, thousands of dollars, this monumental event you've been dreaming about since you were a kid. And then it happens and it's a blur of stress and logistics and Aunt Carol complaining about the seating arrangement. You're exhausted. You barely remember it. You spent more time enjoying the idea of your wedding than the actual day.

The promotion you grinded for. Allllll the money you could make feels better than the money you do make. The degree you earned. The job you finally got.

There's research on this —people report higher levels of happiness anticipating a positive event than actually experiencing it. The fantasy version is always better because fantasy is controllable. Perfect. Reality isn't. Reality has traffic and bad weather and your own exhaustion and the fact that your brain adapts to everything, even the things you swore would change your life.

This is happiness's fatal flaw: it can't survive contact with expectation. Its greatest enemy is not sorrow, no, it's knowing for sure what will happen.

The bigger your expectations, the bigger the letdown. It's almost mathematical. You spend months imagining how amazing something will be, and reality — no matter how good — can't compete with the movie you've been playing in your head.

Think about the last time you felt genuinely, unexpectedly happy. I'd bet money you weren't trying. You weren't in front of a mirror saying three times "I'm a happy person. I'm a happy person. I'm a happy person.", you weren't performing gratitude exercises or optimizing your life for maximum joy. You were probably just doing something ordinary —talking to a friend, working on something you cared about, eating something good, and the feeling just appeared. You weren't chasing it. It found you.

But we don't trust that. We think: if I just get X, then I'll be happy.

If I just get the promotion, then I'll feel successful and everything will click into place. You get the promotion. You're happy for about a week. Then it's just your job, with new responsibilities and new problems, and you're already eyeing the next rung up the ladder.

If I just find the right person, then I'll be happy. You find someone. It's incredible. For a few months. Then the butterflies fade and you're in a normal relationship with a normal person who has flaws and bad days, and you start wondering if maybe they're not "the one" after all. Maybe the right person is still out there, and that's when you'll finally feel the way you're supposed to feel.

If I just make enough money, then I won't be stressed anymore. You make more money. Your expenses somehow rise to meet it. You're still anxious about bills. The number in your bank account got bigger but the feeling didn't change. So you decide you need more money. The target moves.

Every time, the same pattern. You tell yourself this will be the thing that finally delivers. And every time, it doesn't. Not because the thing itself is bad, but because your expectation was so inflated that reality — even good reality — feels like a letdown.

Happiness is too weak to carry the weight of your expectations. It's too fragile. Too dependent on everything being exactly right. Too vulnerable to the gap between what you imagined and what actually is.

And the worst part is you know this. You've experienced this cycle dozens of times. And you still keep doing it. You still keep building up the next thing in your mind, convincing yourself this time will be different, this achievement will finally be enough.

It won't be.

Not because you're doing it wrong. Not because you picked the wrong goal. But because happiness, by its nature, cannot survive the pressure of being the answer to everything. You're asking a fleeting emotional state to bear the weight of your entire sense of meaning and purpose. It was never built for that. It can't hold it.

IV. THE DATA IS CLEAR

Let me show you something.

In 1950, the average American household had one car, no dishwasher, no air conditioning, no television. One income supported a family. Life expectancy was 68 years. Medical care was primitive by today's standards. You couldn't call someone unless you were near a phone attached to a wall.

Today, we have smartphones more powerful than the computers that sent humans to the moon. We have cars with heated seats and GPS. We have air conditioning, streaming services, next-day delivery of nearly anything we want. Two-income households are common, and we're still wealthier than our grandparents by almost every metric. Life expectancy is 76 years. Medical care can do things that would've seemed like magic in 1950.

By every objective measure, we should be happier. We have more. We live longer. We have more freedom. More choices. More comfort. More convenience. More of everything that we've been told leads to happiness.

So, knowing that, let's look at the data.

In 1960, about 1% of Americans reported feeling "not too happy" in their lives. By 2018, that number had more than doubled. Depression rates have increased every decade since the 1950s. Anxiety disorders now affect nearly 20% of American adults. Suicide rates have increased 33% since 1999. Among young people aged 10-24, suicide rates increased 57% between 2007 and 2018.

Antidepressant use in the United States increased 400% between 1988 and 2008. By 2020, over 13% of Americans aged 12 and older were taking antidepressants. That's 1 in 8 people. And these numbers are similar across most developed nations.

Let me put this another way. We are the richest, most technologically advanced, most medically capable, most educated generation in human history. We have access to more information, more entertainment, more comfort, more convenience than any humans who have ever lived. We've solved problems our ancestors couldn't even dream of solving.

And we are miserable.

I'm not cherry-picking data to fit a narrative. You can "feel" it yourself, can't you? Consistent finding across decades of research tells us one thing: material wealth and happiness diverged somewhere around the 1960s and have been moving in opposite directions ever since. We keep getting richer. We keep getting more advanced. We keep getting more comfortable. And we keep getting unhappier.

The hedonic treadmill explains why this happens on an individual level. But we're seeing it play out on a societal level too. Entire nations running on the treadmill together, chasing GDP growth and technological advancement and thinking it will make us happy, and watching our collective mental health deteriorate year after year.

Some people look at this data and conclude that modern life is the problem. That technology is making us unhappy. That we need to return to simpler times. But that's missing the point. The problem isn't that we have too much.

We built an entire civilization around the pursuit of happiness. We structured our economies around it. We measure national success by it. We judge our personal lives by it. We made it the goal.

And the data is clear: it doesn't work.

It's not that we're not trying hard enough. Don't believe anyone who tells you "Yeah, it's just you who's doing it wrong". It's not because you haven't achieved enough. But because happiness does not make a good destination. It's a feeling that comes and goes based on circumstances, and we've been treating it like it's the point of existence.

The data shows us something our ancestors understood: you cannot build a good life around the pursuit of happiness. You cannot structure a society around it. Because happiness is too fragile, too circumstantial, too fleeting to bear that weight.

So what do we do with this information?

We could ignore it. Keep doing what we're doing. Keep chasing happiness. Keep wondering why, despite having everything, we still feel empty.

Or we could look at what came before us. Before we decided happiness was the goal. Before we structured everything around pursuing a feeling. What did humans optimize for when they weren't optimizing for happiness? What did they pursue instead?

Because they pursued something. And whatever it was, it worked better than what we're doing now.

V. WHAT DID OUR ANCESTORS DO

Here's what they didn't do: wake up every morning asking themselves if they were happy.

They also didn't:

- have vision boards.

- journal about gratitude.

- optimize their lives for maximum positive emotion.

- read self-help books about finding their bliss or living their best life.

They didn't measure their worth by how happy they felt on a given day.

Not because they were too primitive to think about it. Not because life was so hard they couldn't afford to care about their feelings. But because they were asking a different question entirely.

The Greeks didn't ask "Am I happy?" They asked "Am I living well?" Eudaimonia, remember, wasn't about feeling good. It was about being good. About fulfilling your potential as a human being. About excellence of character. Aristotle said happiness was a byproduct of living virtuously, not the goal itself. You pursued excellence, you pursued virtue, you pursued meaning, and if you did that well, happiness might, maybe, show up along the way. But it wasn't the point.

The Stoics went further. They said the only thing you control is your character, your response to events, your virtue. Everything else, including whether you're happy, is outside your control. So why would you make it your goal? Marcus Aurelius was the most powerful man in the world, emperor of Rome, and he spent his time writing about duty and self-discipline and accepting what you cannot change. Not about pursuing happiness. About pursuing what was right.

The Buddhists saw desire itself as the problem. Not just desire for bad things, but desire for good things too. The constant wanting, the constant chasing, the constant belief that the next thing will finally make you feel complete. They didn't try to maximize happiness. They tried to transcend the whole game. To find peace that didn't depend on getting what you want or avoiding what you don't want.

Medieval Christians weren't optimizing for happiness either. They were optimizing for salvation, for serving God, for living according to divine law. A priest copying manuscripts in a cold church wasn't asking himself if he was happy. He was asking if he was faithful. If he was fulfilling his duty to God and to the preservation of knowledge. His life had meaning independent of his emotional state.

The Japanese had a concept called "ikigai", your reason for being, the thing that makes you get up in the morning. Not "what makes you happy" but "what gives your life purpose." A craftsman pursuing mastery of his art. A farmer tending to his land across generations. The satisfaction came from the doing, from the excellence, from the contribution, not from the feeling.

Indigenous cultures around the world structured life around community, around responsibility to the tribe, around maintaining harmony with nature and with each other. A Lakota warrior didn't measure his worth by his happiness. He measured it by his courage, his generosity, his service to his people. The concept of "a good day to die" wasn't about being happy. It was about living with such integrity that you could face death with dignity because you had fulfilled your responsibilities.

African Ubuntu philosophy, "I am because we are," put community and interconnection at the center. Your worth wasn't determined by your individual happiness but by your contribution to the collective, by how you upheld your relationships and responsibilities. Personal feelings were secondary to communal harmony.

The Confucian tradition emphasized filial piety, duty to family, respect for hierarchy, cultivation of character. A Confucian scholar wasn't chasing happiness. He was chasing wisdom, righteousness, proper conduct. His life had structure and meaning that didn't depend on feeling good.

Even in early America, before we misinterpreted "the pursuit of happiness" into what it became, the Puritans structured their lives around work, around calling, around duty to God and community. They weren't happy people by modern standards. Life was hard. But they had a framework that made the hardness meaningful. They had something to measure themselves against that wasn't their emotional state.

Look at any culture before the modern era and you see the same pattern. Different values, different frameworks, different gods and philosophies. But none of them put happiness at the center. None of them made feeling good the organizing principle of existence. They all understood that happiness was too unreliable, too fleeting, too dependent on circumstances to build a life around.

And it worked. Not in the sense that everyone was happy all the time. They weren't. Life was hard, and life has always been hard. People suffered. People struggled. People died young and died badly. But the data we have from historical accounts, from letters, from records, suggests that people weren't miserable at the rates we see today. Depression and anxiety weren't epidemics. Suicide wasn't spiking. People seemed to have a sense of meaning and purpose that we've lost.

Why?

Because when you're not chasing happiness, when you're pursuing something else, something more stable, something within your control, you're not on the hedonic treadmill. You're not constantly measuring yourself against an emotional state that's designed to fade. You're measuring yourself against principles. Against values. Against duties. Against the kind of person you're trying to become.

And here's the thing: when you pursue virtue, when you pursue meaning, when you pursue excellence, happiness shows up more often than when you chase it directly. It's like sleep. The harder you try to fall asleep, the more it eludes you. But if you create the right conditions, if you do the things that lead to sleep without obsessing about it, it comes naturally.

Our ancestors understood this. They never bought into the idea that a fleeting emotion should be the organizing principle of existence.

So what did our ancestors pursue instead of happiness? Different things, depending on the culture. Virtue. Honor. Duty. Excellence. Enlightenment. Legacy. Community. Family. God. But notice what all of these have in common: they're not feelings. They're not dependent on your mood. They're not fleeting. They're stable. They're within your control. They give you something to measure yourself against that doesn't disappear the moment you achieve it.

A modern person gets the promotion and thinks "Finally, I'll be happy now." Then adapts to the promotion and feels empty again. An ancient person pursued excellence in their craft and thought "I'm getting better at this." There's no finish line to excellence. You can always improve. You can always develop your character more. You can always serve your community better. You can always be more disciplined, more courageous, more generous.

These things don't fade. They accumulate. They build on themselves. They give you a sense of progress that isn't dependent on circumstances lining up perfectly.

That's what we lost. Not happiness. We actually have more momentary happiness than any generation in history, more pleasure, more comfort, more entertainment. What we lost is the framework that makes happiness irrelevant as a goal. We lost the thing that makes you okay even when you're not happy. The thing that gives your life meaning when circumstances are bad. The thing that lets you suffer with dignity instead of interpreting every moment of unhappiness as personal failure.

We dismantled the entire structure that made human life bearable, and replaced it with "just be happy." And we're shocked that it's not working.

VI. JOY, TODAY'S ALTERNATIVE

So if not happiness, then what?

Finally, after such tarnishing of "happiness as a goal", I think we are ready for the alternative.

I keep coming back to that other word I mentioned earlier. Joy. Not as a synonym for happiness, but as something fundamentally different. Something that might actually work as a goal worth pursuing.

Remember the etymology. Happiness comes from hap, from luck, from circumstance. External. Out of your control. Joy comes from gaudium, from exultation, from a gladness that exists independent of what's happening around you. Internal. Within your control, or at least within your influence.

Happiness says "I feel good because good things are happening to me." Joy says "I feel glad to be alive regardless of what's happening to me."

That distinction matters. That distinction is everything.

Happiness is the moment you get the job. Joy is the deep satisfaction you feel when you're doing work that matters to you, even when it's hard, even when you're tired, even when nobody's watching. Happiness is the wedding day. Joy is the quiet morning years later when you wake up next to someone who knows you completely and chooses to stay anyway. Happiness is winning the lottery. Joy is the accumulation of small moments of meaning that add up to a life you don't want to escape from.

Happiness depends on things going your way. Joy exists despite things not going your way.

Here's what I mean:

Viktor Frankl survived Auschwitz. He watched his family die. He endured conditions that would break most people. He was stripped of everything, his possessions, his identity, his dignity, subjected to unimaginable suffering. And he wrote about finding meaning even there. Not happiness, he wasn't happy in a concentration camp, nobody was happy there. But he found moments of profound meaning. Watching a sunset through the barracks. Helping another prisoner. Maintaining his sense of self despite everything trying to destroy it. He called it the last human freedom: the ability to choose your attitude in any circumstance.

That's joy. Not the feeling of everything being okay. But the sense that you can find meaning even when everything is terrible. That there's something in you that circumstances can't touch.

Or look at people who do hard things by choice. The long-distance runner at mile 20 of a marathon is not happy. Their body is screaming at them to stop. They're in pain. They're exhausted. But ask them afterward and they'll tell you about the joy of pushing through, of proving to themselves they could do it, of the profound satisfaction that comes from voluntary suffering in pursuit of something meaningful.

The parent of a newborn waking up at 3 AM for the fourth time that night is not happy in that moment. They're exhausted. They're frustrated. They want to sleep. But most parents will tell you there's a joy in caring for their child that exists alongside the exhaustion. A sense of purpose and meaning that makes the difficulty worthwhile.

The artist struggling with a piece that won't come together is not happy. They're frustrated. They're doubting themselves. They're wondering why they do this. But there's a joy in the creative process itself, in wrestling with something difficult, in the moments of breakthrough, that doesn't depend on the final product being good or being recognized.

Joy is what remains when happiness fades. It's the thing that makes suffering bearable. It's the sense that your life means something even when it's hard.

And unlike happiness, joy can be cultivated. It can be built, slowly, deliberately, through how you choose to live.

Joy comes from pursuing things larger than yourself. Not because selflessness is morally superior, but because when you're part of something bigger, when you're contributing to something that will outlast you, you stop measuring your life by your emotional state. The cause matters. The contribution matters. Whether you're happy right now becomes less relevant.

Joy comes from depth rather than breadth. One deep friendship gives you more joy than a hundred shallow connections. One skill you've mastered gives you more joy than a dozen hobbies you dabble in. One relationship you've invested in gives you more joy than endless dating trying to find "the one." Depth takes time. Takes commitment. Takes staying when things get difficult. But it pays dividends that happiness never does.

Joy comes from creating rather than consuming. Consuming feels good in the moment. Scrolling social media, watching Netflix, buying things, eating junk food. These give you hits of happiness, brief spikes of pleasure. But they don't leave you with anything. Creating, even badly, even unsuccessfully, gives you something that accumulates. You made something that didn't exist before. That matters in a way that consuming never does.

Joy comes from competence. From getting better at things. From mastery. Not because achievement makes you happy, we've already established it doesn't, but because the process of improving, of seeing yourself become capable of things you couldn't do before, gives you a sense of agency and purpose that doesn't depend on external validation.

Joy comes from aligning your actions with your values. When what you do matches what you believe, when you're not constantly compromising yourself, when you can look at your life and see integrity rather than hypocrisy, there's a satisfaction that runs deeper than happiness. You're not at war with yourself. That peace, that alignment, that's joy.

Joy comes from acceptance. Not resignation, not giving up, but genuinely accepting that much of life is outside your control. That you'll suffer sometimes. That things won't always go your way. That you'll lose people you love. That you'll fail at things that matter to you. When you stop demanding that life make you happy, when you stop treating every moment of unhappiness as a problem to be solved, you create space for a different kind of contentment. A kind that doesn't require everything to be perfect.

Here's the test: Can you find it when things are bad? Happiness fails that test by definition. You can't be happy when things are objectively terrible. But you can have joy. You can find meaning. You can have purpose. You can experience moments of profound gratitude and connection and satisfaction even in the midst of genuine suffering.

That's what makes joy sustainable in a way happiness never is. It doesn't require circumstances to cooperate. It doesn't fade as soon as you adapt. It doesn't get killed by expectations. It's not external. It's not luck. It's something you build, slowly, through thousands of choices about what you pay attention to, what you value, how you spend your time, what you pursue.

The Greeks were right about eudaimonia but wrong about one thing: you can't just pursue virtue in the abstract. You need something concrete. Something you can actually do. The Stoics were right about focusing on what you control but wrong about thinking you can logic your way out of desire. The Buddhists were right about transcending the hedonic treadmill but wrong, at least for most people, about thinking you can just let go of wanting anything.

Joy, I believe, can be our modern synthesis. It's what you get when you take the wisdom of the past and apply it to the reality of the present. You can't go back to being a medieval monk or a Stoic philosopher or a Buddhist ascetic. You live in this world, with its complexity, its choices, its constant bombardment of messages telling you happiness is one purchase away.

But you can choose to find joy around you instead of chasing happiness. You can build your life around meaning and purpose and depth and creation and competence and alignment. You can accept that happiness will come and go, that you'll have good days and bad days, and that's fine, that's how it's supposed to work.

You can stop asking "Am I happy?" and start asking "Am I living a life that means something? Am I building something that matters? Am I becoming someone I respect? Am I contributing something of value? Am I connected to people and purposes larger than myself?"

Those questions have answers that don't change every time your circumstances do. Those questions lead somewhere sustainable.

That's joy. And unlike happiness, it might actually be worth pursuing.

VII. YOUR PERSONAL IMPLICATIONS

I bet every major decision you've made, the underlying question has been some version of "What will make me happy?"

That question doesn't work. We've spent six sections proving it doesn't work. So what are you supposed to do?

The personal implication is simple: you need to replace chasing happiness with cultivating joy.

Let me be clear: happiness is great. I'm not against happiness. Happiness feels good. Enjoy it when it shows up. Celebrate it. Savor it. The problem isn't happiness itself. The problem is making it your priority. Making it what you organize your life around. Making it the goal.

Chasing happiness makes you a fleeting being. You become dependent on circumstances. Cultivating joy is different. It's enjoying what's around you. Accepting it as good, and then making it better. It's about depth.

Accept things, then change them for the better. Accept yourself, then make yourself better. Accept your relationships as they are, then deepen them. Accept your skills as they are, then develop them. Accept your life as it is, then build on it. Not one or the other. Both. Acceptance without change is stagnation. Change without acceptance is never being satisfied. Joy lives in the tension between the two.

You practice control. Take control where you actually have it. You control your effort. Your attention. Your choices. Your responses. You don't control outcomes, but you control inputs. So you act deliberately. You make choices and you own them. You don't let yourself be a puppet to your feelings. Feeling anxious doesn't mean you avoid the thing. Feeling bored doesn't mean you quit. Feeling excited doesn't mean you chase it. Not feeling excited doesn't mean you don't chase it. You feel what you feel, then you choose what to do based on what matters to you, and then you will feel good and joyous anyway.

Invest, commit. and build. You can't have deep relationships if you keep one foot out the door. You can't develop real competence if you switch focus every time something gets hard. You can't create anything meaningful if you refuse to commit time, attention, resources to one thing long enough to see it through. So you pick things that matter to you and you stay. You invest in them. You commit to them. You build them. That depth, that accumulation, that's where joy lives.

You find joy in the process. Not just the outcome. The work itself. The conversation itself. The practice itself. The building itself. External goals are great. Necessary even. Have them. Pursue them. But don't make yourself dependent on achieving them. Find joy in the doing. The marathon runner finds joy in running, not just in finishing. The artist finds joy in creating, not just in being recognized. The parent finds joy in raising their child, not just in them turning out well. The process is where you spend your time. If you can't find joy there, you're going to be miserable most of your life waiting for outcomes.

You let yourself be deeply moved by life. You don't protect yourself from feeling. You don't stay numb. You don't play it safe emotionally. You let things touch you. A conversation that matters. A piece of art that hits you. A moment of connection. A realization that changes how you see something. The beauty of something ordinary. The weight of something difficult. You let it in. You let it affect you. Most people spend their lives defended, protected, careful not to feel too much because feeling is risky. But joy requires being open to being moved. It requires letting life reach you. When you're closed off, when you're defended, when you're just going through the motions, there's no joy. Just hollow routine. But when you're open, when you're present enough to be affected by what's happening, when you let yourself care about things even though caring makes you vulnerable, that's when joy appears. Not happiness that depends on things going right. Joy that comes from being alive enough to be moved by life itself.

You don't act based on fear alone. You can feel fear. Fear is information. But you don't let it make your decisions. You're afraid of the hard conversation, you have it anyway. You're afraid of failing at the thing you care about, you try anyway. You're afraid of being vulnerable, you open up anyway. Not to be courageous, but because fear-based decisions keep you small, keep you protected, keep you from depth. Joy requires risk. It requires being willing to care about things that could hurt you. It requires choosing connection over safety, growth over comfort, depth over distance.

You build depth in relationships. You choose people and you actually invest in knowing them, in being known by them. You have hard conversations instead of avoiding them. You show up when it's inconvenient. You choose them again when the initial excitement fades. Deep relationships create satisfaction that doesn't evaporate. A relationship that has depth doesn't make you happy every day. Some days it's frustrating. Some days it's boring. But there's a solidity to it, a sense of "this matters, this is real" that gives you something to stand on. That's joy.

You build yourself up, look at who you are honestly. See the gaps between who you are and who you want to be, and work on closing them. The process of developing yourself, of becoming more capable, more honest, more aligned with your own standards creates forward motion. You're not static. You're evolving. Find better standards to judge yourself by. Not happiness. Not feeling good. But competence, integrity, depth, contribution. Measure yourself against those. Align your actions with your actual values. Start being honest. If you say family matters but you never see them, family doesn't matter to you. Your behavior is your values. Look at what you actually do. Look at where your time actually goes. Look at what you actually prioritize when there's a conflict. Those are your real values. Now ask: are those the values I want? Is this who I want to be? If not, close the gap. One choice at a time. Choose the thing that aligns with who you want to be, not the thing that will make you happy right now. That integrity, that coherence between stated values and lived values, that's joy.

You build your skills up. Pick things that matter to you and get actually good at them. Good enough that you can see your own progression. Practice is often tedious. Learning is often frustrating. But it can be joyous.

You create things. Create for an audience if you want. Approval is great. Recognition is great. But the act itself is also joyous. Making something that didn't exist before does something to you. It proves you're not just consuming. You're contributing. You're adding instead of just extracting. Write. Draw. Build. Cook. Make music. Whatever. Just make. That agency, that proof of your own creative capacity, that's joy. And yes, share it. Let people see it. Want them to like it. There's joy involved in every step of creation.

You connect to purposes larger than yourself. Live life large. When you're part of something bigger, when you're contributing to something that will outlast you, you stop measuring your life by your momentary emotional state. Could be your family. Could be your community. Could be a cause you care about. When you're connected to something larger, the question shifts from "am I happy?" to "am I contributing? Am I doing my part?" Those questions have answers that don't change based on your mood. That stability, that sense of being part of something beyond yourself, that's joy.

You engage with difficulty that's meaningful. Not difficulty for its own sake. Not suffering as a virtue. But difficulty in service of something you care about. That willingness to do hard things because they matter to you creates purpose and meaning that runs deeper than feeling good.

You develop the capacity to be present. Actually here. Not mentally somewhere else, not checking your phone, not running calculations about whether this moment is making you happy. Here. Now. This conversation. This work. This moment. Joy requires presence. You can't experience it if you're constantly elsewhere. Be in your life, not watching it from a distance.

Here's what changes: you stop asking "will this make me happy?" You start asking "will this deepen something that matters to me? Will this let me build something? Will this connect me to something larger? Will this align with my values? Will this keep me engaged with life?"

You're in a job that's fine but not exciting. The happiness framework says keep looking for something that'll finally feel right. The joy framework says: can I develop competence here? Can I contribute something? Can I find meaning in the work itself, not just the outcomes? Can I build relationships with people I respect? If yes, find joy here. If no, if it's actually destroying you, if there's nothing here worth developing, then leave. But leave because it's actually wrong, not because it's not making you happy.

You're in a relationship that's become routine. The excitement faded. You're not unhappy, but you're not happy either. You start wondering if you're with the right person. The happiness framework says maybe you're not, maybe there's someone else out there who'll make you feel the way you used to feel. But you felt that way with this person too, at the beginning, and it faded then too. It'll fade with the next person. And the next. The joy framework says: can you build depth here? Can you know each other more fully? Can you choose each other beyond the feeling? If yes, find joy here. Depth. Presence. Choosing again. If no, if there's actually nothing here, no real connection, no shared values, just comfort and fear, then leave. But leave because there's nothing real, not because the butterflies faded.

You chase happiness, you become a reaction to circumstances. You cultivate joy, you develop an internal state that persists regardless of what's happening around you. You accept what is, then you make it better. You take control where you have it. You invest and commit and build. You let yourself be moved by life. You find joy in the process, in the journey, in life itself.

And let me be clear about what cultivating joy doesn't mean. It doesn't mean never scrolling social media. It doesn't mean never watching Netflix. It doesn't mean always doing hard things. It doesn't mean rejecting pleasure or comfort or ease. Scroll sometimes. Watch TV sometimes. Take the easy path sometimes. Rest. Relax. Enjoy mindless things. That's fine. That's human. The point isn't to optimize every moment. The point is to not make those things your priority, your organizing principle, your answer to "what makes life worth living?"

That's the personal implication. Stop organizing your life around a feeling designed to disappear. Start cultivating a state of being that can persist regardless of circumstances. Stop being a puppet to your feelings. Take control. Build depth. Find joy. Not as a destination. As a way of being in the world.